Common Assessment Tools for Outdoor Recreation Settings

This is an excerpt from Outdoor Leadership 3rd Edition With HKPropel Access by Bruce Martin,Mary Breunig,Mark Wagstaff & Marni A. Goldenberg.

The final portion of this chapter focuses on three common assessment tools that can be applied in various contexts: checklists, rubrics, and surveys. Checklists are a quick, easy way to document an individual’s skills and accomplishments. Compared with checklists, rubric tools provide a more descriptive record of an individual’s performance based on predefined criteria. A well-designed rubric clearly outlines expectations that can be assigned a numeric value to quantify results. Checklists and rubrics are used in diverse situations such as evaluating technical skills, judging one’s teaching ability, assessing employee performance, or appraising the quality of a written assignment. A well-made, properly implemented survey solicits valuable information needed for a variety of uses in a program assessment. Designing and implementing a quality survey is a fundamental skill outdoor leaders must exercise in any job environment.

Developing Checklists

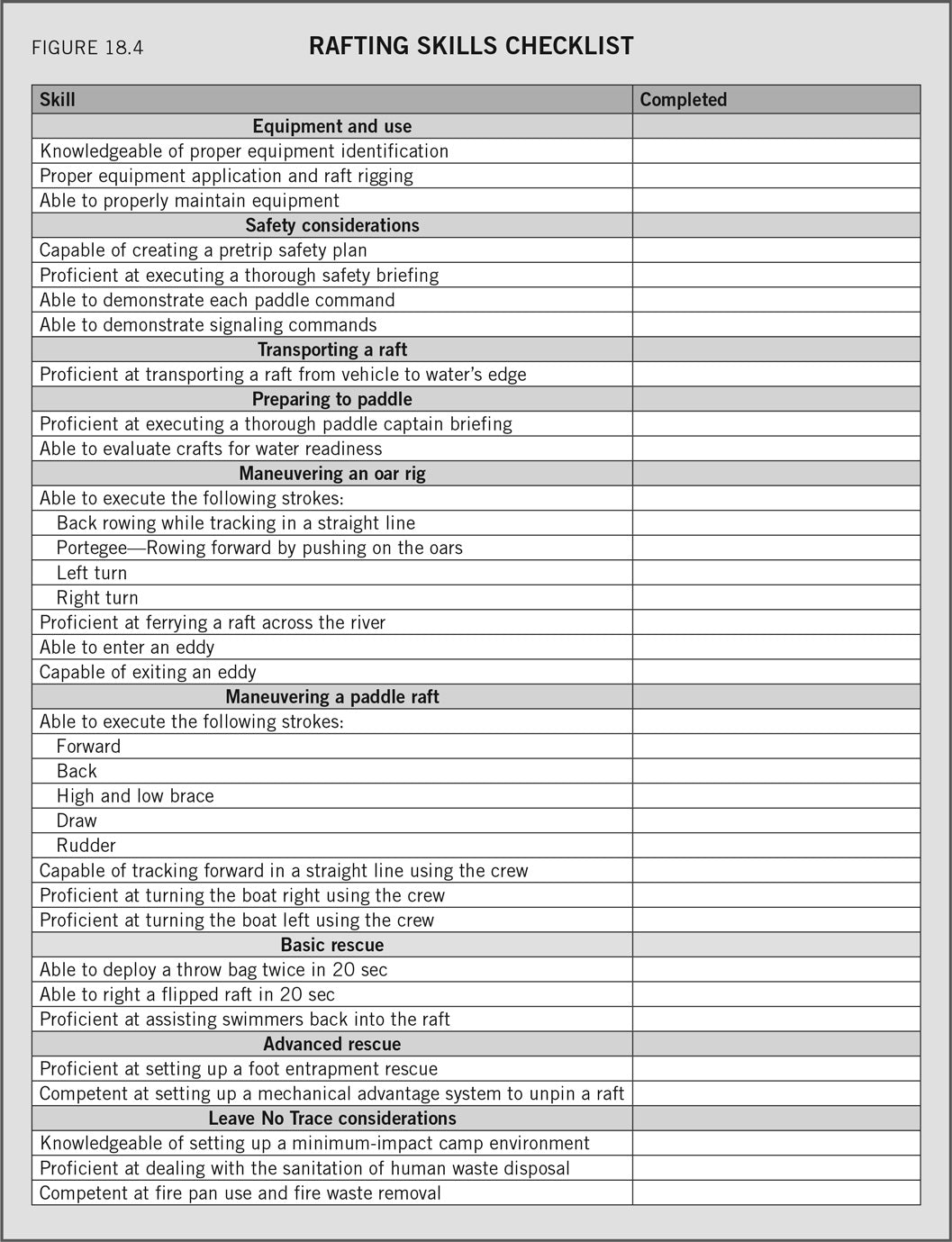

Checklists, which are simple to design and implement, are popular tools for those charged with the task of documenting observable criteria. To create a foundation for this discussion, refer to figure 18.4, a skills checklist used to assess rafting guides in training (Pelchat and Kinziger, 2009). This classic checklist design highlights the technical skills necessary to become a whitewater raft guide. The company trainer schedules preseason training sessions for all new hires. On the last training trip, the trainer assesses each new employee on each skill on the checklist. If a trainee demonstrates minimal competency or better, the trainer checks off the skill. This process is straightforward and simple from an assessment standpoint because the trainee either demonstrates or does not demonstrate the skill.

Looking at this system critically, one might think something is missing. Where is the quality rating for the observed performance? In other words, how well or at what level did the trainee demonstrate the skill? Was the demonstration excellent or below average? This concern can easily be addressed by adding a Likert-type scale to the evaluation, such as the common 5-point scale (5 = outstanding performance, 4 = good performance, 3 = fair performance, 2 = needs significant improvement, 1 = demonstrates no grasp of the skill). Some evaluators prefer a 4-point scale because it forces a more definitive evaluative decision. No middle value exists, so a person’s performance falls either at a 2 or below or at a 3 or above. The Likert-type scale adds a descriptive measurement and scoring mechanism to the process.

Other questions surface in this discussion when integrating more descriptive measurements. What are these descriptors based on? What constitutes outstanding performance? Scores could be based on measurement criteria found in standards of the American Canoe Association’s rafting curriculum. Or the performance criteria might be described in a staff manual. If curricula and standards are already in place, the checklist assessment is a more valid and effective tool. Using a checklist without clearly defined criteria becomes a subjective process driven entirely by the evaluator’s judgment and potential biases. However, this is not always a problem. It depends on what is being assessed. For example, during Alyce’s two-week trips, she may be interested in verifying her students’ performance of basic outdoor living skills. She is not necessarily interested in assessing levels of competency; however, she does want to use the list as a motivator to challenge her students to engage in all skills. At the beginning of the trip, she tells her students to practice their skills as much as possible. When they feel confident enough to perform them under her direct observation, they should inform her so she can check them off.

If used correctly and in proper contexts, the checklist is a useful method. However, as pointed out, a more powerful tool is needed when the quality or level of performance must be assessed and documented. This is when a rubric assessment tool is needed.

Developing Rubrics

Rubrics differ from simple checklists in that the design includes specific performance criteria or desired outcomes that serve as the basis for measurement. The design uses a matrix format that includes defined levels of quality to assess performance criteria. Outdoor leaders who can design and use rubrics significantly improve their ability to implement an assessment system. A substantial amount of literature exists for outdoor leaders who wish to use this effective tool (Andrade, 2005; Angra and Gardner, 2018; Boston, 2000; Goodrich, 1997; Schoepp et al., 2018; Stevens and Levi, 2013).

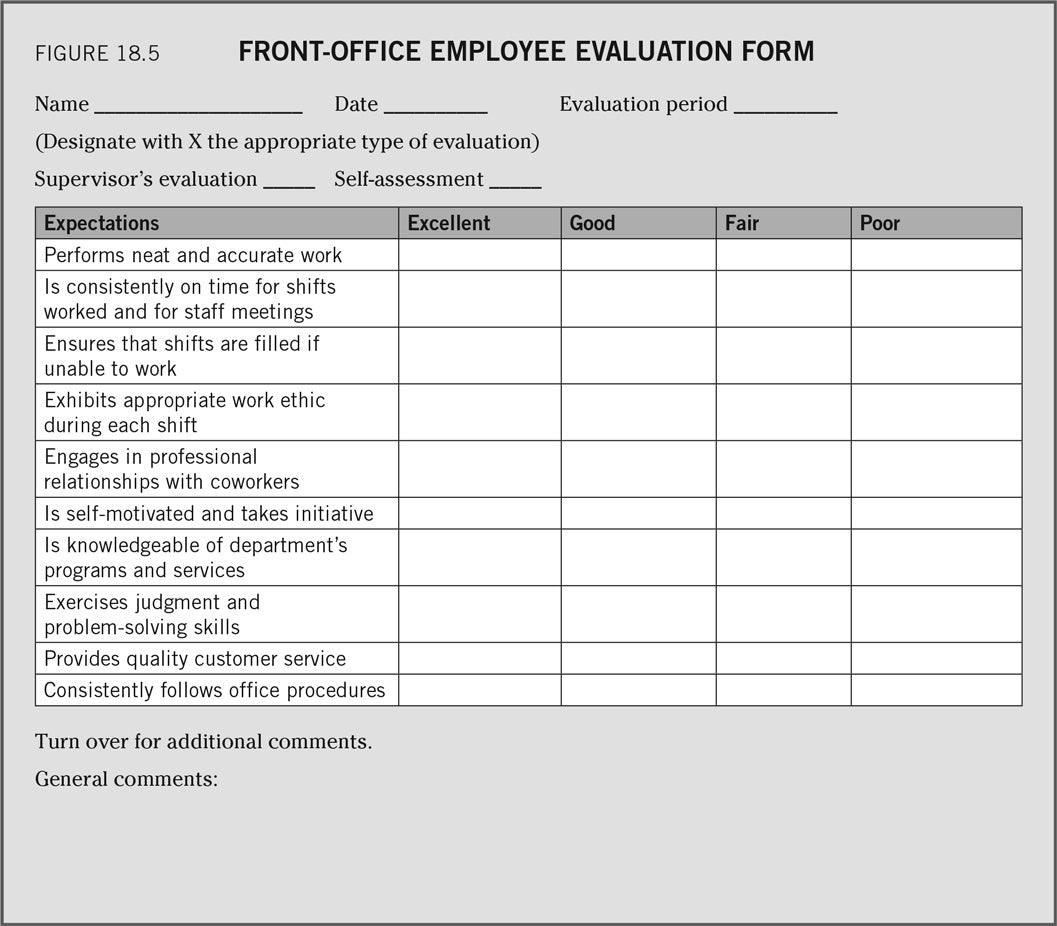

To begin to understand rubrics as evaluation tools, refer to figures 18.5 and 18.6. Figure 18.5 illustrates a conventional checklist combined with a scoring mechanism used by a university outdoor program administrator to assess front-office student workers. Front-office workers are expected to provide basic program information, register customers for trips, and accomplish simple administrative tasks. The design of this checklist allows the supervisor to assign a quality rating (excellent, good, fair, or poor) to each of the evaluation points. This form provides 10 items or performance expectations for front-office workers.

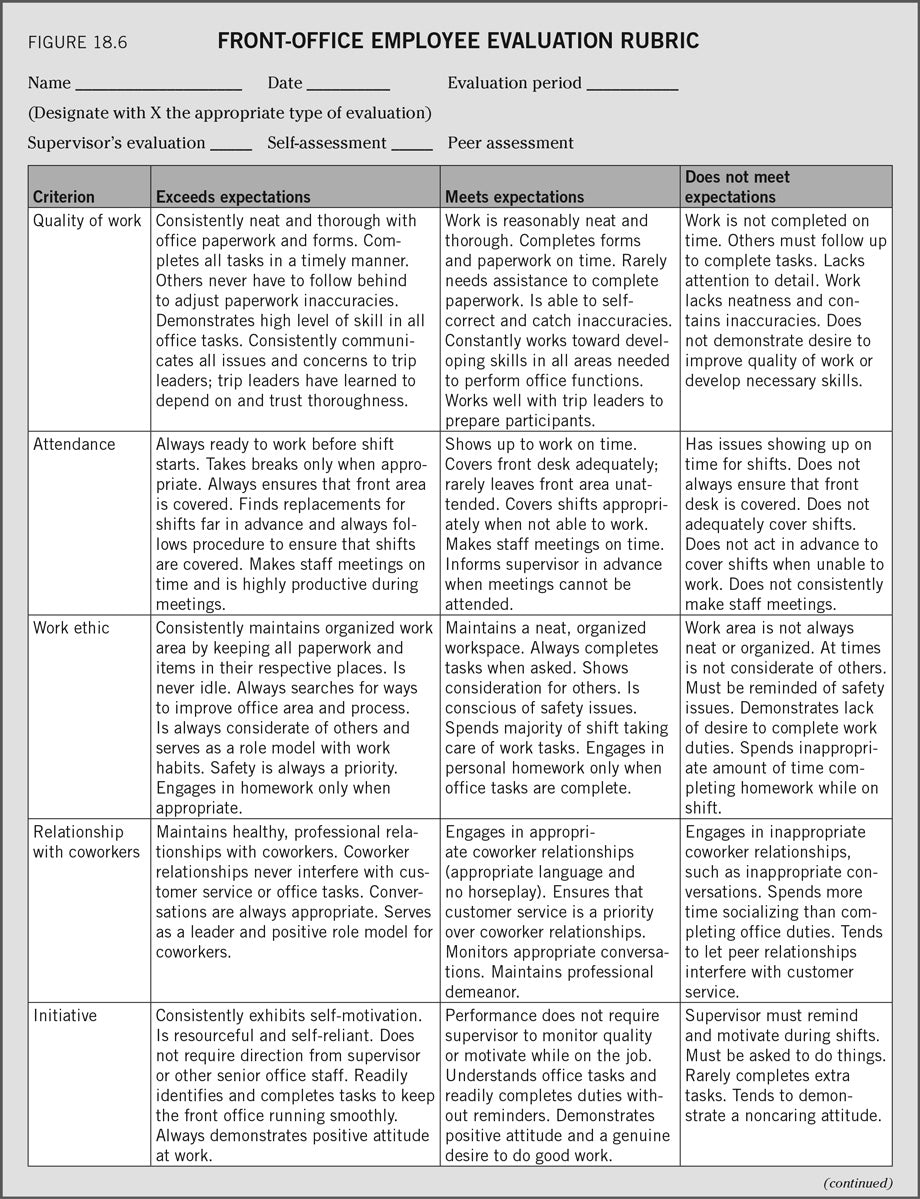

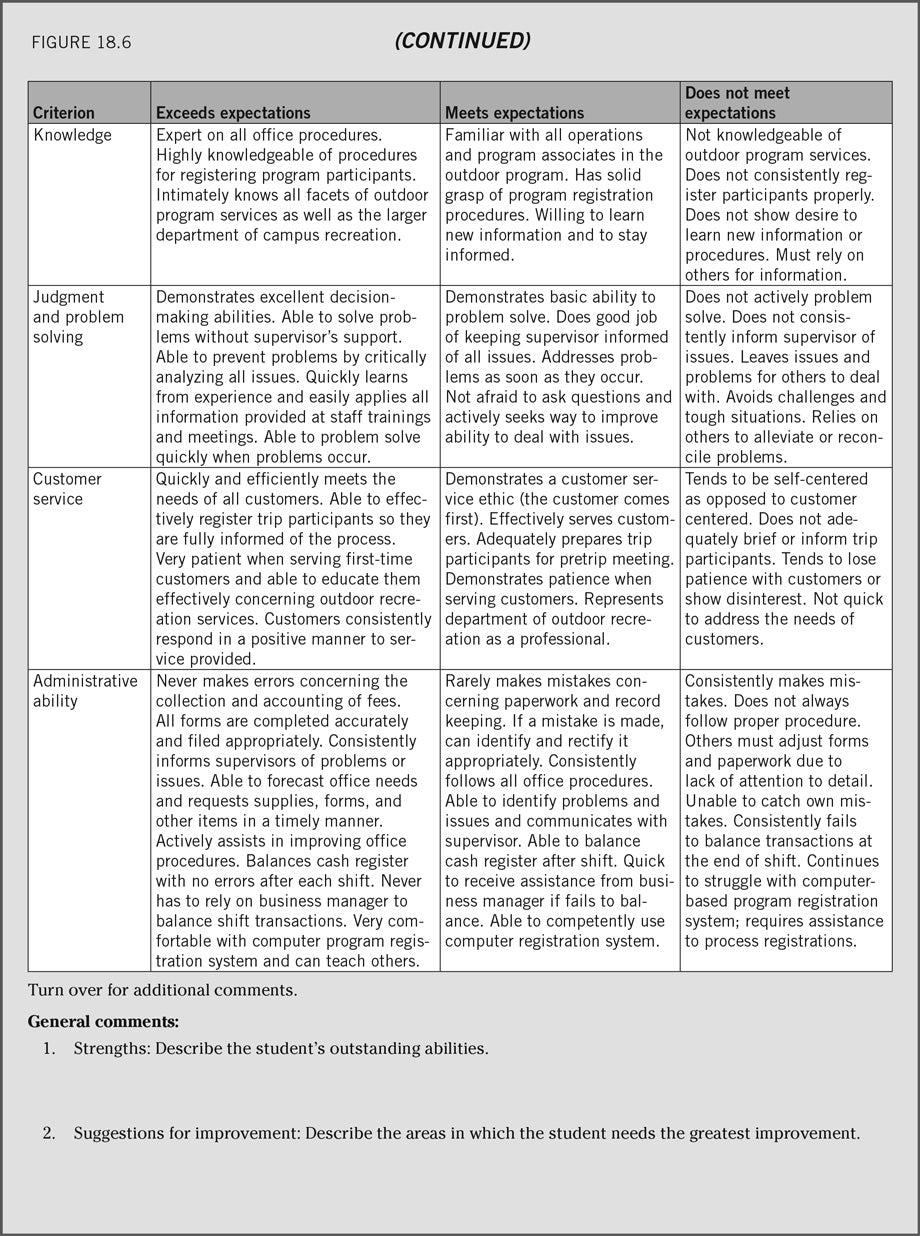

A rubric format provides a more effective way to evaluate and clarify the expectations for the front-office position. Figure 18.6 illustrates a rubric designed from the same 10 expectations used in figure 18.5. The 10 expectations are modified and clarified into 11 specific performance criteria or desired outcomes. The desired outcomes are then qualified using three levels: exceeds expectations, meets expectations, and does not meet expectations. Qualifying the outcomes with detailed descriptions promotes several benefits. First, student workers have a clear and concise understanding of supervisor expectations for each outcome. Second, the supervisor has the option to integrate specific expectations into the rubric based on factors found in the working environment. For example, worksite-specific issues such as completing homework while working, balancing peer–coworker relationships, and mastering a computer-based registration program are all issues specific to this work environment. Finally, employees have a clear ideal to strive toward to exceed expectations, thereby promoting feelings of success and pride. This approach provides the necessary information for employee growth and development.

Notice that figures 18.5 and 18.6 can be either completed by the administrator or completed as a self-evaluation. The rubric design provides a much more meaningful way to self-evaluate, because the carefully articulated quality levels do not leave as much room for interpretation. Employees can self-evaluate with more accuracy, which promotes quality conversation when reviewing the results with the supervisor.

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW